_This is not a review of the book of the same title. No, really, it's not. It's a manifesto, first espoused here on this semi-read blog, of how I, a mild-mannered thirty-something writer, considered polite by most, shall, in actuality, and with an abundance of commas, one day destroy all the civilized planets. Seriously, that's what it is. Why are you laughing? Well, okay. It's not a manifesto, and I fully lack the world domination gene, so, I suppose... reluctantly and with much sighing... I should talk about the book of the same title. But this isn't a review.I Shall Destroy All The Civilized Planets! is a collection of comic strips of the cult figure Fletcher Hanks. Hanks is a legendary figure among comics historians and aficionados. His work appeared under many pseudonyms and in many publications in the 1930's, when comics were still in their infancy. He has been routinely characterized as an "Ed Wood of the comics world", a grossly inaccurate metaphor and primarily only used because it sounds catchy. Hanks was more the nascent comics world's Kilgore Trout, the struggling, pulp science fiction writer of Vonnegut's novels (an alter ego of Vonnegut himself).Collected in this volume (and its companion You Shall Die By Your Own Evil Creation) are the complete archived material of Hanks, including his most lasting and popular creation Stardust, a supernatural superhero with unlimited strength and intelligence. The plot lines are always thin and formulaic: a group of gangsters conjure the most convoluted and ill-advised schemes to achieve world domination--invisible fusing fluid to freeze all transportation in order to enslave all Americans and take over the world; the creation of a tidal wave to drown every living creature--plots which are usually defeated by Stardust, who travels from his home planet to stop the crimes.

_The most characteristic element of Hanks' works were the wildly inventive and violent means by which the hero, be it Stardust or Fantomah (the female ruler of the jungle), or Big Red McClane (the honorable lumberjack) or any other two-dimensional stock hero, uses to stop the crimes. The elaborate tortures are the results of Hanks' depraved and haunted, destructive mind, one that the editor of the collection, Paul Karasik, reveals in his afterword. Karasik, in his efforts to interview this long-lost comics hero of his, discovers an address of a man named Fletcher Hanks Jr., himself a decorated air force pilot and writer of a memoir about his time serving as a pilot in WWII. It turns out this was Hanks' son, who proceeds to tell Karasik the real story of his father: According to a review and feature article in The Believer from August 2007, "Fletcher Hanks, nicknamed “Christy” after Baseball Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson, was, by all accounts, a louse. An alcoholic and a wife-beater, Hanks once kicked his four-year-old son, Fletcher Jr., down a flight of stairs. The punt and subsequent tumble left the boy unable to speak intelligibly for five years. 'My old man didn’t like runts,' explained the younger Fletcher. The boy was runty, to be sure, and suffered from rickets, but his dad’s rage was something beyond reckoning. 'My father,' he said, 'was the most no-good drunken bum you can find.'" The senior Hanks abandoned his family in the 30's, stealing his son's money as he left. He was found frozen to death on a park bench in New York in the 70's. The afterword, in fact, is the only semblance of emotion in the collection, other than the outsized rage and disturbing lengths of righteous indignation foisted upon the victims. Hanks did not rid himself of his demons on the page alone. It is an emotional reminder that sometimes the artist doesn't match up to the art itself. In the case of Fletcher Hanks, given the id-driven elaborate vengeance plots, we should not be surprised that the person and the art itself match. The work seems to be mostly a mechanism for Hanks to put on paper the more violently depraved machinations of his mind. The tragedy is that Hanks didn't stop at the page. The work is strange, twisted, raw. But Hanks' influence on the future of comics cannot be minimized. The rise of Flash Gordon, the Justice League, much of the Marvel universe of the 60s can be seen as a result of Hanks' work, albeit much tamer. In my trips to the library, I passed by this title in the graphic novel shelves frequently but would ignore it; it seemed raw, campy, D-list superheroes. However, I also like to consider myself a self-imposed champion of the obscure, of the outposts of literature, those forgotten works that no one else knows about.The eminently humane Kurt Vonnegut wrote of this collection, "The recovery from oblivion of these treasures is in itself a major work of art." I like to delude myself that I'm in good company for having read this collection.

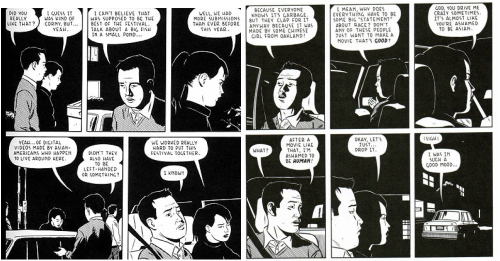

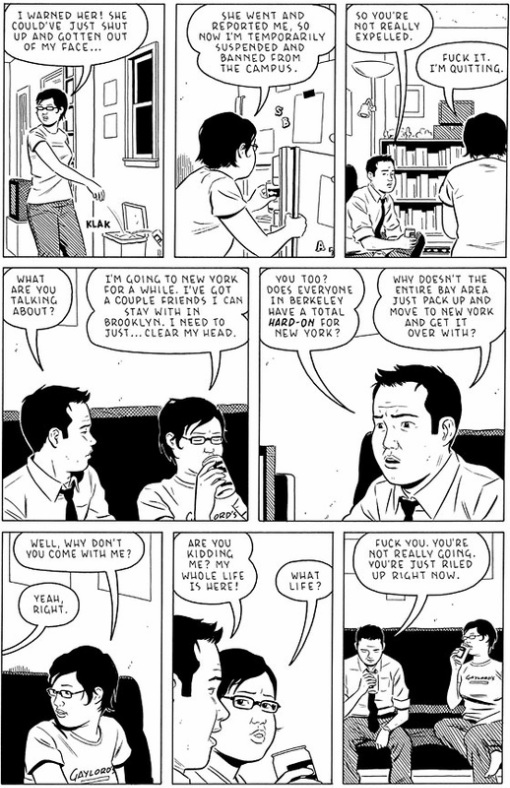

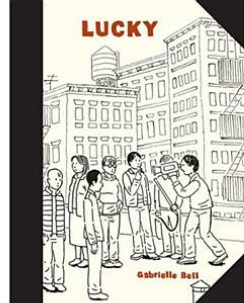

2011 is my year of the graphic novel. Early on I distinguished between comics and graphic novels. I wanted to read those stories that seemed to have more realistic and less fantastical, superhero based story lines. (That could be groundings for a future blog post or, hell, even a doctoral thesis: what distinguishes literary from genre fiction? Why isn't genre fiction considered literary, etc.) A friend recommended Gabrielle Bell and, after seeing my review of Lucky, asked if I had read his other recommendation: the Optic Nerve series. I told him the library did not have it, but they did have Tomine's Shortcomings. "You read Shortcomings?" Shortcomings, although his first full-length book, is not usually the first book used to introduce someone into Tomine. Something comparable would be recommending Finnegan's Wake to someone who has never read Joyce, or proposing to someone on the first date: it's generally not a good idea, you want to ease into things like that. Shortcomings is generally considered Tomine's masterpiece, at least until his next book comes out. It's ostensibly about Ben Tanaka, one of the most unlikable protagonists in recent memory. Ben is a dick. He's critical of everyone and everything; he picks fights with his long-time girlfriend Miko, he mocks the films in the festival she organized; and, like most flawed narcissists, he has a magnifying glass on everyone's faults but a blind spot towards his own.

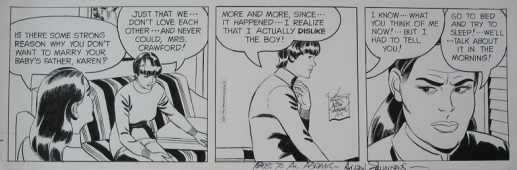

That said, he's also very smart, and very loyal to the few friends he has (especially Anna, with whom he has some of the best verbal sparring, primarily because she calls him on his caustic bullshit). He can be charming, as he woos two different girls later in the story. He's not violent and doesn't partake in illegal, dangerous activities. The disintegrating relationship between Ben and Miko is the catalyst Tomine uses to explore race and culture, and how societal and cultural expectations affect self-identity, if at all. As you can see, it's pretty light reading. At one point Miko accuses Ben of deliberately harboring hatred towards Asian culture, thereby implicating both Ben and Miko as objects of his ire. She points out that all the porn Ben owns is of white, blond women, an accusation that his fantasies do not include Asian women, and therefore he does not like Asian women. Ben denies this and in the next scene Ben is criticizing the technical quality of the DVD itself. However, the first two dates he goes on after Miko moves to New York to pursue film, are with white, blonde women, perhaps affirming Miko's accusation all along. Does this make Miko right? Does Ben have a type? Does Ben have issues with his own culture and what is expected of him? Why should Ben, as an Asian male, be expected to date Asian women? Should there be any self-inflicted expectations based on culture? To his credit, Tomine does not answer any of these questions, nor does he judge any of his characters. He doesn't show Ben in a needlessly negative light or as a misunderstood genius who's just too hurt inside to show his tenderness. Ben's a complicated, caustic human being. Tomine's graphic novels work like a stageplay. We don't know the internal motivations of the characters, or their background; we're just observers. I originally intended to write a negative review given the expectations I had after reading the dust jacket. It reads: By confusing their personal problems with political ones, Ben and Miko are strangely alone together and oddly alike... Being human, all too human, they fail to see that what unites them is their hypocrisies, their double standards. This gray zone between the personal and political is a minefield Tomine navigates boldly and nimbly. The charged, volatile dialogues that result are unlike anything in Tomine's previous work or, for that matter, comics in general. I saw the societal and cultural implications, and thought it raised great questions about culture and race and self-identity that are very rarely covered in literature, let alone comics. I thought it raised strong questions about sexuality and gender within that cultural landscape as well. I just didn't see the "political" implications. But I couldn't bring myself to write a negative review: it is insightful, provocative, well-written. The characters are three-dimensional, complex, sometimes unlikeable. The drawings fit the story, they possess a minimalist Mary Worth style. Compare below: I mentioned this to my friend, who, for the record, is Asian. Most of the people he had discussed the book with saw the political implications. He also said those same people were Asian. And so, in that moment, during our conversation about Shortcomings, the cultural insights and observations Tomine discusses were being acted out in the coffee shop, an unintentional meta-narrative-cum-commentary.

But that raised a different question for me. If I didn't catch everything that supposedly was explored in the book, did that make me a bad reader? Should we hold ourselves accountable to dust jackets? Obviously, no, on both accounts. We should not hold ourselves accountable to a dust jacket, and it doesn't make us bad readers if we "don't get it."

My issue came not with the book or with Tomine. It was with the dust jacket and my interpretation of the word "political". I think of "political" and I think of lawmakers, politicians, and the daily political theater of our Congresspeople. Perhaps naively (intransigently?) I think the word "politics" should be relegated to this arena, and not mixed in with what has become accepted lingo: cultural politics, sexual politics, office politics. Let's leave the word "politics" where it belongs: with the politicians.

I shouldn't hold the dust jacket or a single word against the book. Tomine didn't write the dust jacket. The publisher did. Tomine did write the contents inside the book, though. And this book, and Tomine's work I whole-heartedly recommend.

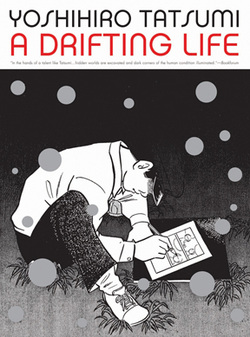

I wish I knew more about Tatsumi before I started reading the book. I took it out of the library due to a few factors: 1) 2011 is my Year of the Graphic Novel; 2) I had not seen a graphic novel with as epic a page count as this (855, including the appendix--I'm a notes reader), so I thought it would be an ambitious read; 3) the scope of the book seemed interesting for a graphic novel, and ambitious writers, even if they fail in their ambitions, always appeal to me, sometimes more than safe writers; 4) it was in the same area in the library as a few other books I had been looking for, so serendipity and random selection I suppose played its part; 5) it was published by Drawn and Quarterly, who I have quickly realized are almost flawless in their book selections. Drawn and Quarterly is the graphic novel equivalent of Matador or 4AD Records: if you like one or two releases from this label/publication, chances are you will like almost everything they produce. The book chronicles Tatsumi's (or Katsumi's, as he calls himself in the book) life starting from when he began writing four-panel comic strips as an early teen, to the point when he became a major force in the Japanese manga marketplace, and his gekiga became an accepted form. The fact that I knew so little about this author, the history of manga, and his notable place in the history and evolution of manga appealed to my omnivorous sensibilities: I am naturally drawn to the unfamiliar. If someone is not too daunted by an 800+ page book, I highly recommend it. And since it is a graphic novel, that 800+ page count (and subsequent reading time) can be significantly reduced. However, I cannot give this bildungsroman 5 stars, though this is primarily based upon my own Western reading conventions and prejudices. There are many times where Tatsumi introduces information or a character, and tells us in an aside in the panel itself what is to happen with that character. For instance, in the beginning of the story, a young Katsumi is asked by his father, a delivery man, to make his deliveries for him to a couple of women. Katsumi does, and the women read the letters attached to the delivery. An aside in the panel says that Katsumi would not understand the role of these women in his father's life until much later. But the author then drops that thread. We never return to it, and are never told anything about those women, or what the significance of the letters to them were. There is also a small plot thread involving a young female classmate of Katsumi's sister, who accompanies her to school everyday. After a certain time the classmate comes to the house late repeatedly. It is inferred this is in order to have a 30-second interaction with Katsumi, who always answers the door. We are told in another panel aside that someone would try to play matchmaker between Katsumi and this girl four years later, but we are never shown the results of this romantic possibility. There are other instances where future information is given the reader but we never reach the point where this information is relevant. Katsumi also provides historical, societal, and cultural information to the reader throughout the book, like a pop-up information of what was happening in Japan at the time politically, societally, and culturally. Blocks of pages are reserved every so often to let us know what films were showing, what music was popular, how Japan was recovering from WWII and becoming an industrialized power: a veritable Japanese historical encyclopedia. Perhaps the biggest compliment I can give the book is that it makes me want to read more about Tatsumi, and to try to find some of his early manga/gegika stories, if only to fill in the blanks of the stories he began in A Drifting Life. Perhaps, much as I found the book while rummaging through library shelves in search of something else, other books, perhaps I will discover some of Tatsumi's early works in the same manner. goodreads review

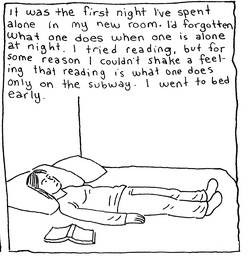

Continuing my 2011 fascination with graphic novels, I read Gabrielle Bell's Lucky yesterday. Much has been written about her minimal cartooning style, her insights and lack of romanticism about life as a twenty-something artist in NYC, which paradoxically makes her work (and her) charming. Much has been made of her capturing the spirit of an entire generation and lifestyle of people, while still living that particular lifestyle. I will not do any of these in this unorthodox review, for it has been stated in many reviews. Two quotes from the collection resonated with me the most, especially in light of my own transition to living in the city. They also reflected two of my biggest loves--reading and running--and how my relationship with them has changed while living in the city:"I tried reading, but for some reason I couldn't shake a feeling that reading is what one does only on the subway." "I decided to go jogging instead. I often go jogging when I feel like I have no control over anything." For insights like those, for cutting through the red tape of our brains much faster than any visit with a psychologist ever could, I'll choose Lucky.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed